For the past couple of years I’ve been researching classrooms where teachers and students have taken on game design as a vehicle for learning. I've read extensive international research (and some rhetoric) on games and game design and its potential for learning. I’ve befriended game developers, and lurked curiously in their conferences and online groups, And I did the most challenging and humbling thing of all: I worked with others to design a game.

Now, when I talk to teachers new to game design about why they should consider supporting their students to do it, I start with this reason: "because it’s hard". Not hard as in “don’t do it”, but hard as in “that’s why it’s worth doing” - the same way John F. Kennedy talked about going to the moon in 1962.

I’ll admit going to the moon might be a little harder, ok a lot harder, than designing a game. But unlike going to the moon, designing a game is something that’s certainly within the capabilities of children when they have the right tools, support, and timeframes to achieve this. Based on what game-designing students and teachers say, it’s definitely one way to “organise...the best of our energies and skills” in a classroom, and for many young people it is a “challenge [they are] willing to accept”.

Teachers, or any adults, who have never tried to make a game (digital or otherwise), may not understand why game design is so challenging, and thus so worthwhile. Adults who are leery of games may especially underestimate the rich learning opportunity that game design offers.

In my next few blog posts, I want to explain some of the things I’ve learned about “learning through game design”. I want to share some of the benefits that teachers and students can gain through this process, as well as some of the reasons why game design is challenging in any setting, and may be an especially challenging thing to do in schools.

The iterative design process

Here’s one of the big reasons game design can be a scary proposition for schools. At the heart of game design lies a truly iterative design process. No game can be devised and created by mapping out a plan from start to finish. All game designs start with an idea, or several ideas, that have to be prototyped, tested, changed, retested, tweaked, and refined through many cycles of playtesting.

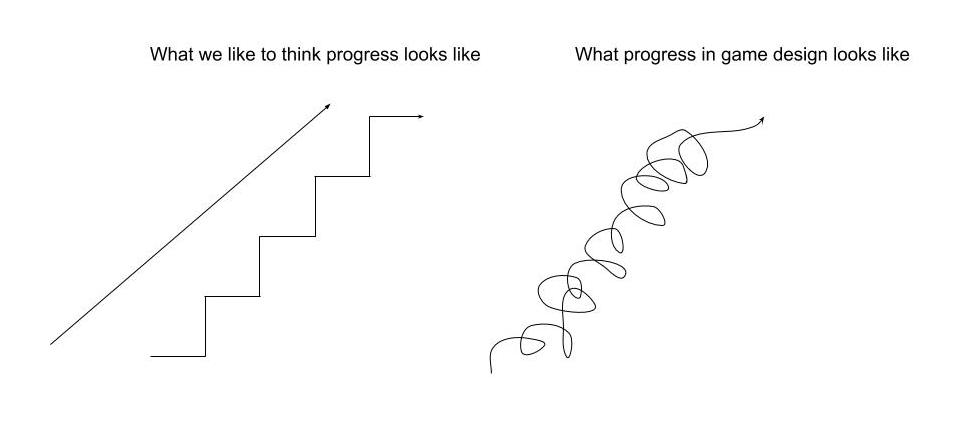

What I have observed is that many adults struggle to truly embrace what "iterative design" really means in practice. I’ve noticed this amongst teachers, researchers, policymakers, and many other professions where iterative design is not the way we have been taught to do things. We may be much more comfortable with a linear process that gives us a feeling of security that there are clear steps, stages, and outcomes to get from A to Z.

Even those of us who support the idea of iterative design “in principle” can find it challenging - even scary - to operate this way. Not only is it hard to predetermine what the final outcome might look like, it’s also hard to predetermine the exact order of steps and the pathway that it will take to get there. It means being able to trust in the process, and not be put off by uncertainties and ambiguities along the way. (I know how hard this can be - I have been there myself!).

In the Games for Learning project, we’ve seen how important it can be for teachers to feel supported by their peers and colleagues, or to find like-minded teachers or researchers. Teachers need support when they are feeling uncertain about what to do next, or when “the pressure is on” for students to complete a game, and expected timeframes bear little resemblance to reality.

While game design is a complex process, it’s not totally random and chaotic. There is a process, it’s just that that process does not look much like the way we do a lot of things in schools. I’ve adapted a picture that you might have seen around the internet describing what progress really looks like, compared to how we think it looks:

In my next post, I’ll get into more detail about the game design process, what that can look like in the classroom, and what teachers and students in the Games for Learning had to say about it.

Tell us what you think!

If you've ever designed a game, or supported students to do game design, does the post above reflect your experiences of the process? Let us know what you think in the comments below.

Astronaut graphic Copyright: mcrad / 123RF Stock Photo

Add new comment